POSTED February 2, 2024

12 Black dance makers and their contributions to Ailey

Alvin Ailey had a vision for his Company to be a mixed repertory company, particularly to give other Black choreographers a place to showcase their work. For Black History Month, Ailey is recognizing twelve of them.

Mr. Ailey was dedicated to seeking out and commissioning rising talent to create work for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and in doing so created one of the first successful repertory companies for modern dance. "It was my idea, especially with the Black choreographers, to keep works in repertory," Mr. Ailey said. Part of his motivation was to dispel the notion that Black dance referred to a single sensibility, and to show that African American choreographers possessed a wealth of aesthetic and thematic diversity.

Here are twelve choreographers whose works became a part of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s repertory and who collectively broadened the landscape of modern dance.

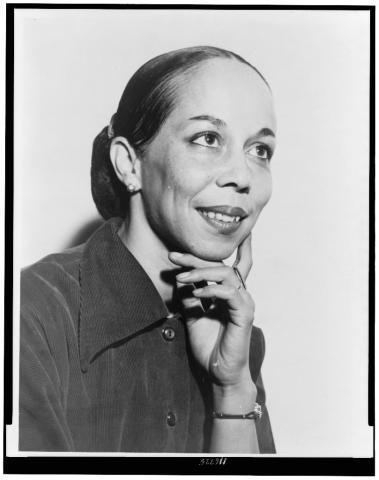

Katherine Dunham (1909-2006)

Katherine Dunham did more for the exposure of Black dance forms in American concert halls than any choreographer before her. An anthropologist and choreographer, Dunham drew from her travels in Africa, the Caribbean, and the West Indies. She learned folkloric dance forms from her travels and combined them with modern dance to create a distinctly African American form of concert dance. Through her touring company and her schools, she inspired a generation of Black dancers, including Alvin Ailey, who first saw the Katherine Dunham Dance Company in 1945 at the Biltmore Theater in Los Angeles.

Dunham was an outspoken anti-segregationist, successfully suing two hotels for refusing her accommodation. After a performance in 1944 at a theater which did not allow Black audiences, she told the crowd, “I will have to say that it is impossible for us to return to you […] we cannot appear where people such as ourselves cannot sit next to people such as you.” In 1972, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater commissioned Dunham’s work Choros, a dance based on a Brazilian Quadrille, first performed in 1943. In 1987, the Company premiered the evening length work The Magic of Katherine Dunham.

Talley Beatty (1918-1995)

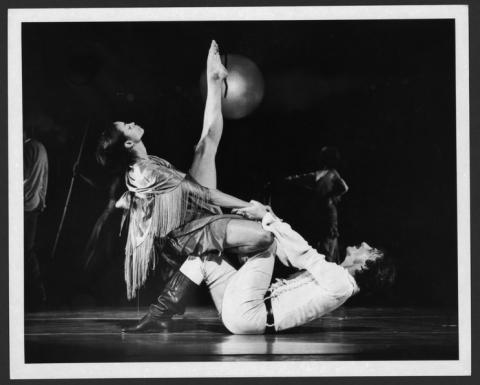

When he was starting out as a dancer, Talley Beatty trained with modern dance icons Martha Graham and Katherine Dunham. He then toured with the Katherine Dunham Dance Company for five years before starting his own career as a choreographer. Beatty’s works combine modern, ballet, and jazz movements to create a distinctive personal style. His ballet The Road of the Phoebe Snow (1959), set to music by Duke Ellington, is perhaps his most famous. It depicts a community living alongside railroad tracks in the Midwest, both abstractly and dramatically conveying the feeling of the world passing them by. Several of his works made it into the Company’s repertory with the last addition being Stack-Up, which depicts the emotional 'traffic' in a community that is stacked on top of each other.

As well as making his mark with contemporary works for ballet and modern dance companies—such as Dance Theatre of Harlem, Batsheva, and Ballet Hispanico—he was a renowned choreographer of Broadway musicals. He received a Tony Award nomination for Best Choreography in 1977 for Your Arms Too Short to Box with God.

Donald McKayle (1930-2018)

Before becoming a renowned choreographer, Donald McKayle began his dance education in his teens at the New Dance Group in New York City, where he learned from Martha Graham, Merce Cunningham, and Pearl Primus, among others. He clearly had talent and performed with Martha Graham and José Limón, then was chosen by Jerome Robbins to be the dance captain for the original production of West Side Story.

Growing up in East Harlem, McKayle aspired to show the experiences of Black Americans on stage and create dances that confronted racial injustice. His work Rainbow 'Round My Shoulder (1959), which became part of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater repertory in 1972, depicts a Southern chain gang and the violence inflicted on Black men seeking freedom. When most dance companies were still overwhelmingly white, McKayle insisted on working with a diverse cast of dancers. “My dance companies were always multiracial because of my deep belief that injustice, prejudice, discrimination and ethnic persecution stems from fear and ignorance of the other, the alien that looks different,” McKayle said. “All that matters to me beyond the technique of the dancer is his passion, expression, and his soulful approach.”

Janet Collins (1917-2003)

Janet Collins was a ballerina, choreographer, and teacher who holds the esteemed acclaim of being the first Black ballerina to perform with the Metropolitan Opera. She was initially offered a position with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, but refused when the director Leonard Massine told her she’d have to paint her skin white. As a Black ballet dancer, Collins confronted the prejudiced views of audiences and critics who believed Black dancers were physically incapable of executing ballet technique.

Before her time at the Met, she danced with Katherine Dunham and presented her own work, a combination of classical ballet and modern dance set to Mozart and Black spirituals, at the 92nd Street Y in 1949. Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater recognized Collins’s legacy in 1974 and invited her to stage two works on the Company: Spirituals (1949) danced to Black spirituals much like Revelations, and Canticles, a new work staged for the Company.

Pearl Primus (1919-1994)

Like Katherine Dunham, Pearl Primus was a dance anthropologist as well as a dancer, choreographer, and teacher who became a leading figure in presenting dance of the African diaspora. Her works drew from her African heritage—her grandfather was a member of the Ashanti people in Ghana—and she traveled to Africa and the Caribbean to learn all of their traditional dance movements. She was the first Black student at the New Dance Group in New York, a school that trained dancers with the moto “Dance is a weapon,” meaning that dance should be created with social and political awareness and not just art for art's sake. Among the many teachers she encountered there, Asadata Dafora was particularly influential with his performances of African ritual dances.

Inspired by Dafora, Primus choreographed her own staged versions of African ritual ceremonies, beginning with African Ceremonial (1944). She also spent time in the deep south immersing herself in the hardships of African American life at the time. She used her experiences to create Strange Fruit (1945), a meditation on lynching, and The Negro Speaks of Rivers (1944), inspired by Langston Hughes’ poetry. In 1974, Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater commissioned two of Primus’ works: Fanga (1949) based on a Liberian dance of welcome, and The Wedding (1961), based on Congolese ritual dances.

Geoffrey Holder (1930-2014)

Geoffrey Holder was a chameleon: an accomplished dancer, choreographer, actor, composer, designer, and painter. He was born in Trinidad and Tobago in 1930 and by the age of seven had begun dancing for his brother’s dance troupe, the Holder Dance Company, eventually becoming the company’s director.

He first came to New York in 1954 and joined the cast of House of Flowers just as Alvin Ailey and Carmen de Lavallade, whom he would eventually marry, had done the same year. In House of Flowers, Holder played a Haitian Voodoo spirit of death named Baron Samedi, a role he revived in the 1973 James Bond film, Live and Let Die. As an actor, he performed in an all-Black staging of Waiting for Godot in 1957. He won two Tony awards for his work on the musical The Wiz, for direction and costume design. As a choreographer, Holder combined Afro-Caribbean dance with modern and ballet techniques. His work often took inspiration from historical figures, such as Haitian folk painter Hector Hypolite, whom Holder depicted in his ballet Prodigal Prince (1967) for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

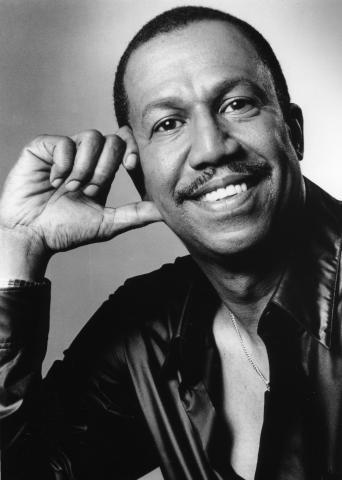

George Faison (1945-present)

George Faison danced with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater from 1967 to 1970, but first saw the Company perform when he was a student at Howard University. “I can’t even imagine what I wanted to do before that,” he said. Faison stunned audiences with his dynamite performances in the “Sinner Man” trio of Mr. Ailey’s Revelations.

After leaving the Company, he formed his own, the George Faison Universal Dance Experience. To earn money, he choreographed music concerts, working with Roberta Flack and Stevie Wonder, along with Earth, Wind, and Fire. His greatest success came when he choreographed the musical The Wiz, winning a Tony for his choreography. He returned to choreograph for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater numerous times, creating ballets scored to rock and R&B music such as Suite Otis (1971), Hobo Sapiens (1976), and Tilt (1975), among others.

Read more about George Faison in an interview with American Theatre where he talks about his influences, his work with pop stars, his time with Alvin Ailey, and the love of his life.

Eleo Pomare (1937-2008)

Pomare was a divisive and radical figure in the world of modern dance—a Black choreographer who openly disdained the limitations of white critics and subverted expectations of what constituted Black dance. “I didn’t stick to the cliché of what a Negro is supposed to look like and behave like on stage,” he said. “I have something to say and I want to say it honestly, strongly and without having it stolen, borrowed or messed over.”

His work Missa Luba (1965) critiqued the colonizing missionaries in Africa and was danced to a Latin Catholic Mass performed by a Congolese Boys Choir. A year later he choreographed Blues for the Jungle (1966) as a direct response to the 1964 Harlem riots, depicting the drug-use and routine imprisonment that had become standard for Harlemites. Pomare also created Dance-mobile in 1967, a traveling stage on the back of a flatbed truck that brought concert dance directly into Harlem and the Bronx, communities where concert dance wasn’t easily accessible. For Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater Pomare created Blood Burning Moon in 1978. He also staged two works for Ailey II in 1992: Hex and Plague.

Bill T. Jones (1952-present)

Bill T. Jones is one of America’s most prolific living choreographers. He is the cofounder of Bill T. Jones/Arnie Zane Dance Company and is now the Artistic Director of New York Live Arts. His work uses both dance and spoken word to confront urgent socio-political issues. One such piece, Still/Here (1995) caused controversy for having performers living with HIV openly address their status on stage. New Yorker dance critic Arlene Croce infamously dismissed as “victim art,” causing a fierce backlash—Jones’ partner and co-founder of their company, Arnie Zane, died from AIDS in 1988, making Croce’s comments wildly insensitive and severely limited in recognizing what dance as an art form could be.

Over his career, Jones has challenged such critics and revealed the systemic racism within the institutions of modern and postmodern dance. “Many white people do not know what it means to be a black body among white bodies,” he said during a conversation with Yvonne Rainer, a prolific postmodern choreographer in her own right. “That’s why I thought it was very important to take the Avant Garde that I respect, but to hold it up and say this too is a product of the same American system that gave you George Floyd.” Jones has choreographed two works for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater: the fast-paced, jazzy Fever Swamp (1983); and How to Walk an Elephant (1985), a collaboration with his partner Arnie Zane and a satirical take on Balanchine’s Serenade, which also upset the critics.

Ulysses Dove (1947-1996)

Ulysses Dove choreographed works that played between form and expressive meaning. He started out as a dancer, the first and only one to dance in both Alvin Ailey's and Merce Cunningham's companies. In 1973, after seeing Mr. Ailey’s Love Songs, Dove knew he wanted to join Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. When he did, he quickly became one of the Company’s leading dancers.

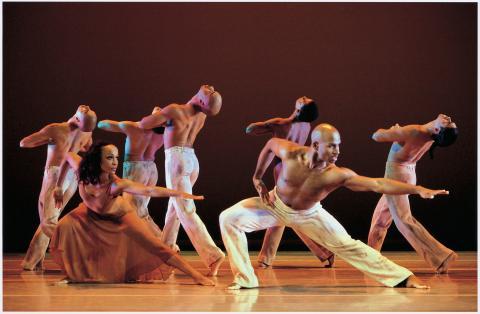

At Mr. Ailey’s urging, Dove turned to making dances. In 1980, he created Inside, a solo for Judith Jamison which she described as “one of the hardest pieces I’ve ever done.” Shortly after, he left the Company to make work for New York City Ballet, American Ballet Theater, and Dutch National Ballet. His dynamic works Bad Blood (1984), Vespers (1986), and Episodes (1987) became audience favorites in Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s repertory. In 1995, Dove returned to choreograph a new work for the Company, Urban Folk Dance, a ballet about two passionate neighboring couples. “I’m interested in pure movement that expresses pure emotion,” he told an interviewer in 1989. “I'm not trying to get across a meaning. I’m trying to get across an experience.”

Jawole Willa Jo Zollar (1950-present)

Choreographer Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s work embraces African forms of dance and music. She grew up in Kansas City, Missouri, and trained with Joseph Stevenson, a former dancer with Katherine Dunham. When Zollar moved to New York City in 1980, she briefly danced with Dianne McIntyre’s company Sounds in Motion before founding her own group, Urban Bush Women in 1984. Her company is a women-centered group dedicated to telling stories of the African diaspora through traditional and modern Africanist dance forms.

“I was being buoyed by Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde, the whole womanist movement, the black women writers, the Africanist writers,” Zollar said. “It made me want to claim this space of the pelvis even before I understood how or the ways that I would do that.” In 1988, Zollar choreographed Shelter, a reflection on the depravations of unhoused people to the drumming of Junior “Gabu” Wedderburn. In 1992, Judith Jamison approached Zollar about setting the piece on Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater— she accepted and recast the work to feature all women. Zollar also choreographed C# Street-Bb Avenue for the Company in 1999.

Camille A. Brown (1979-present)

Using forms of dance from the African diaspora, Camille A. Brown creates thought provoking work that is deeply rooted in ancestral and contemporary African American narratives. In 2006, she founded her own dance company, Camille A. Brown and Dancers, but didn’t stop there—going on to choreograph for other dance companies, Broadway, opera, film, and television.

She directed and choreographed the Broadway revival of for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf (2019), making her the first Black woman to direct and choreograph a Broadway show since Katherine Dunham in 1955. She also holds the claim of being the first Black artist to direct a mainstage production for the Metropolitan Opera with Fire Shut Up in My Bones (2021). Brown created her first work for Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater in 2007 called The Groove to Nobody’s Business, depicting an encounter on a subway that transforms from pedestrian movement to feats of street dance virtuosity. Brown’s other works—The Evolution of a Secured Feminine (2007) and City of Rain (2010)—also became part of the Company’s repertory.