Jacqueline Green in Cry Photo by Paul Kolnik

POSTED May 1, 2024

Cry opens with a cloth held aloft, draped heavily between the dancer’s upraised hands, shielding her from the audience. She is a column. Her hands open, parting the fabric and revealing her face, full of dignity and strength—full of the world. She walks forward, deep earthbound steps crossing left and then right. She seems pulled by some unseen force, yet she's not tentative. The cloth becomes a rope of bondage, a washcloth for scrubbing the floor, a head scarf of nobility. She feels the weight of the heavy fabric in her hands, yet her arms remain strong. She stays planted to the ground as she is willed this way and that—her body like the ocean’s tide, drawn by the moon.

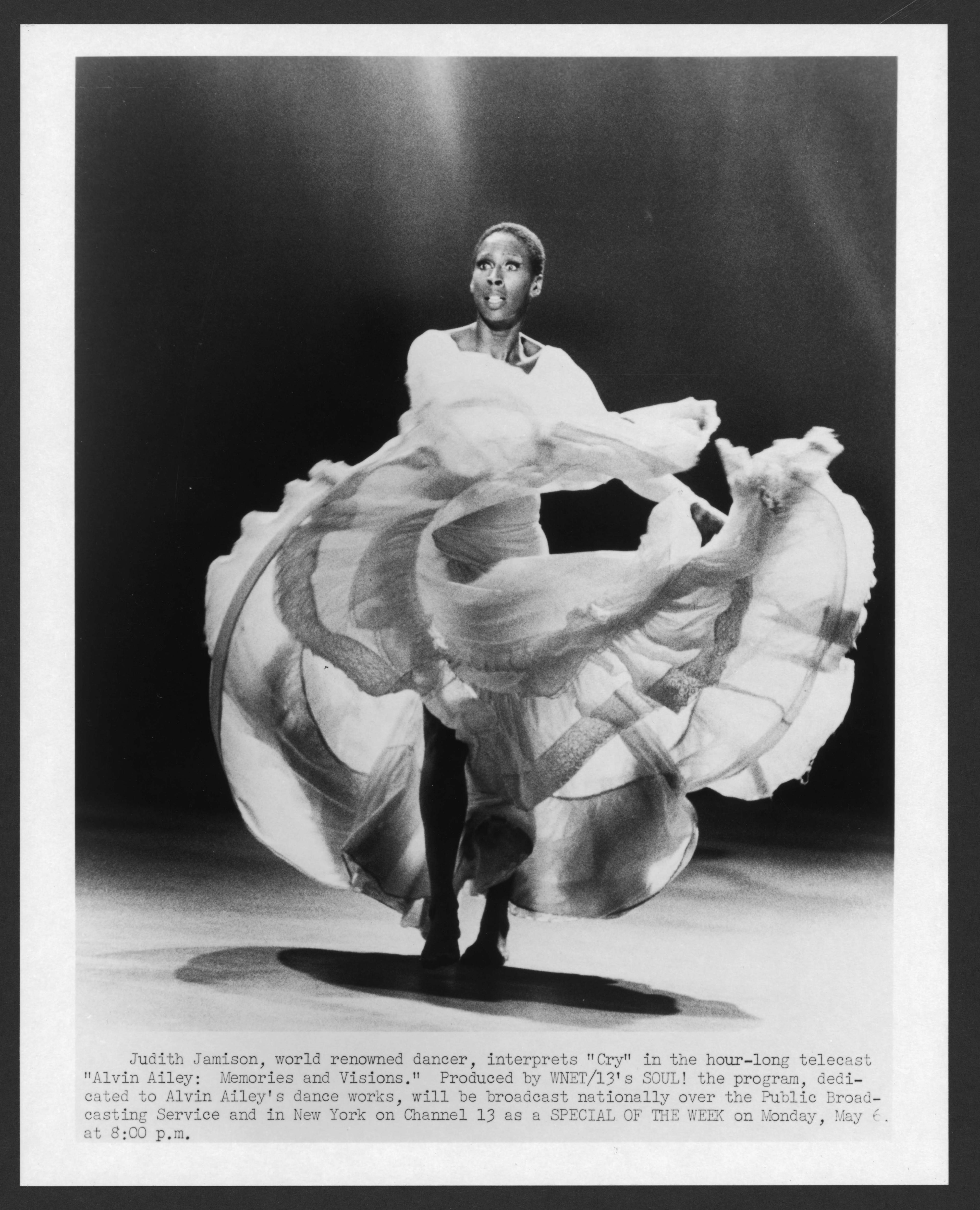

In the opening section of Cry, Alvin Ailey’s 1971 work originally choreographed for Judith Jamison, the cloth becomes a symbol for the weight of the world that Black women carry on their shoulders, “especially our mothers,” Mr. Ailey wrote. He famously choreographed Cry as a 59th birthday present for his mother, Lula, and tasked Ms. Jamison with evoking the enduring strength that Black women have held for generations—he drew inspiration from an image of a woman cradling her starving child in the Biafran war that he saw in a magazine and from young dancers he saw dancing in a bar during a Company tour to Zaire in 1967. However, Ms. Jamison said, "He never even told me about the dedication. I didn’t know until I read the program notes,” referring to Mr. Ailey dedicating the work “to all Black women.”

As much as Cry had been a gift for Mr. Ailey’s mother, it was also his gift to Ms. Jamison—a piece that honored her arresting presence, her physical power, and her inexhaustive emotional gravity. The day before the ballet was to premiere, during the technical rehearsal, she tried on her costume for the first time, only to realize that the high-waisted dress was impossible to move in and was not attractive. She and Mr. Ailey spent the hours before the performance finding another costume, settling on two white long-sleeve leotards (two were required because of the length of Ms. Jamison’s arms) onto which a skirt from the “Wade in the Water” section of Revelations was sown. Once she was in the costume, she’d have to be cut out of it.

Ms. Jamison had never run the piece from start to finish until the premiere, when she was in front of an audience. She had no idea the depths she would have to pull from to get through the 17-minute piece. The hardest part was the final section—the celebratory dance of emancipation to “Right On, Be Free” by the Voices of East Harlem—at which point she was already sweating and exhausted.

If I had known how hard this dance was when I was doing it the first time I went out, I wouldn’t have come out on that stage.

After the first performance of Cry on May 4, 1971, at New York City Center, the audience applauded Ms. Jamison for ten minutes (about half the length of the solo itself). It was an immediate triumph, the perfect marriage of Mr. Ailey’s choreographic focus and Ms. Jamison’s virtuosic dancing. “Rarely have a choreographer and dancer been in such accord,” Clive Barnes wrote of the premiere in The New York Times, “for here crystalized is the story of the Black woman in America told with an elliptic and cryptic poetry and a passionate economy of feeling.” It was almost immediately likened to Revelations for its power and timelessness, yet it stood on its own as a showcase of a single dancer’s abilities.

Eighteen different women have taken on Cry since Ms. Jamison inaugurated it. Each has faced the daunting task of making the work her own, reaching down to the root of herself and letting that presence fill the stage. Cry challenges dancers to trust that their bodies know the movement, so that they can focus on being a human first and imbue the dance with raw emotions.

Jacqueline Green in Cry Photo by Paul Kolnik

Sara Yarborough in Cry Courtesy of the Ailey Archives

Linda Celeste Sims in Cry Photo by Paul Kolnik

Deborah Manning in Cry Photo by Jack Mitchell. (©) Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. and Smithsonian Institution

Constance Stamatiou in Cry Photo by Paul Kolnik

Donna Wood in Cry Photo by William Hilton

“You can’t go into this piece just as a dancer,” said Constance Stamatiou, who first danced the solo in 2017. “During this [rehearsal] process, as much as I thought I was emoting and telling a story, there were little things—it was always the preparation into a turn or something—where [Ms. Jamison] was like ‘Uh-uh, I saw that coming.’ It really made me think of [approaching] it more as a human and not so much as a dancer.”

“She wanted to take the institution of dance out of it,” Jacqueline Green said of Ms. Jamison’s teaching, “so it was really about the story and the intention.”

“One of the hardest things to do is not to finish the dance looking exhausted,” said Nasha Thomas, who taught the solo to younger dancers after she'd performed it. “I tell the dancers to conserve their energy and build slowly, otherwise they'll end up with their bodies on one side of the stage and their lungs on the other.”

Cry is a work that Ms. Jamison has delighted in sharing with generations of dancers. “I choose women for the ballet who can carry its weight,” Ms. Jamison said of casting Cry. “They must be able to fill the stage from the very beginning. They must understand their individuality and dig down deep to deliver something new to the audience. That secret self has to come out. There's no hiding place.”