POSTED June 2, 2025

Behind the Scenes of The Holy Blues

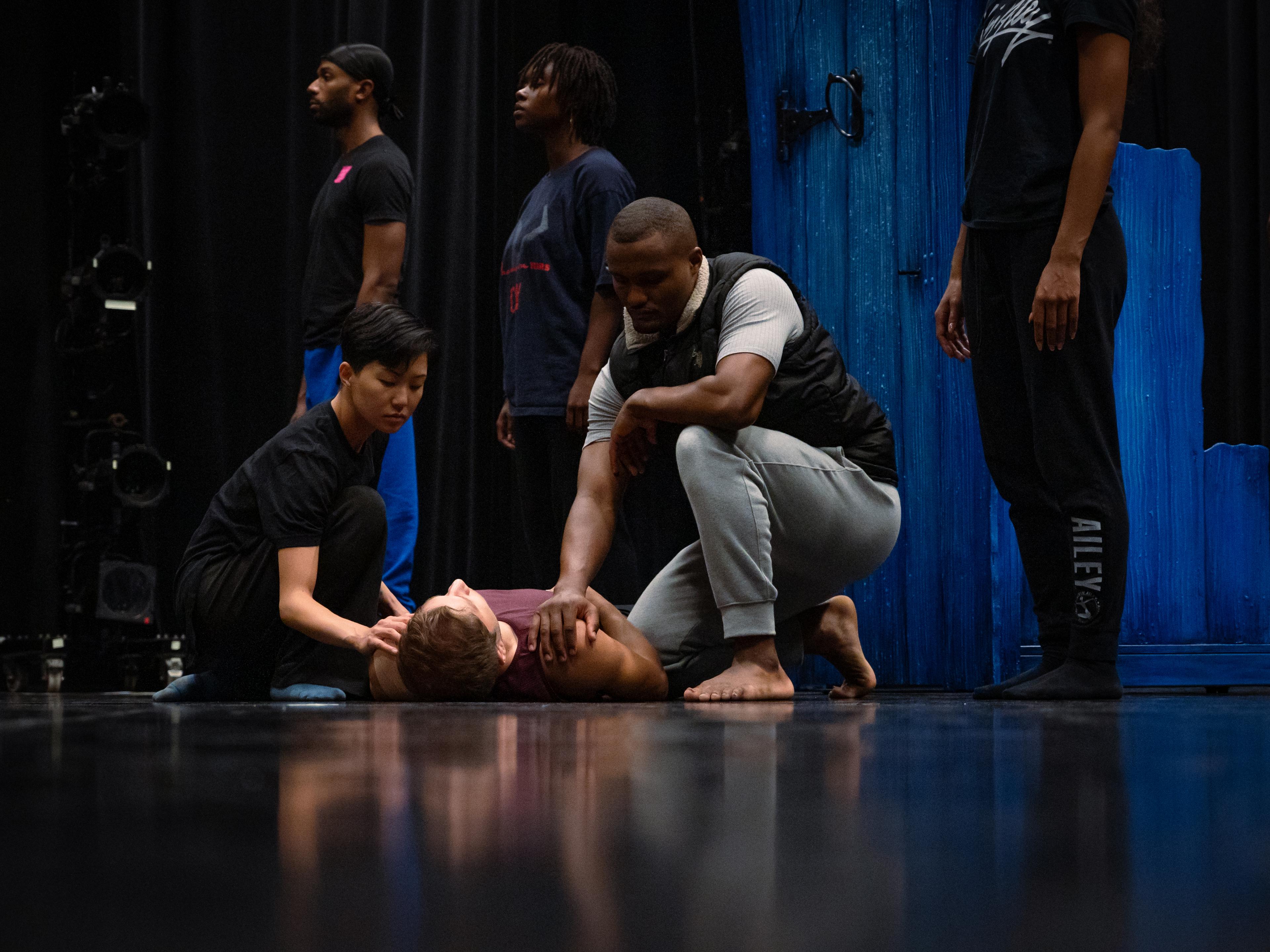

The Holy Blues, conceived and directed by 2025 Ailey Artist in Residence Jawole Willa Jo Zollar in collaboration with choreographers and company dancers Samantha Figgins and Chalvar Monteiro, will have its world premiere at Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater's 2025 BAM season, June 5–8. Monteiro and Figgins discuss their collaboration with Zollar and the ideas behind the work.

What does it mean to you to be collaborating with Jawole Willa Jo Zollar on The Holy Blues and premiering on the BAM stage?

Monteiro: I'm still pinching myself, thinking about the creative team I'm a part of, and being guided and mentored by the fabulous Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, as well as Vincent Thomas [assistant director], Shari Stokes [collaborative dramaturg], and then to work with my best friend since college Samantha Figgins has been a dream. To present a work on this stage where I've seen many illustrious artists and companies perform and present their voices, I am thrilled to add my voice and my name to the list of folks that have contributed to the Brooklyn audience. I'm also excited to be a part of the season because it's not often that Ailey gets to have a presence in both boroughs. I'm really happy to lend my voice to not only this work but also to stir the imagination and the curiosities of our audiences and see what conversations are generated in response.

Figgins: For me, this is a full circle moment. I just can't believe it. I could get emotional thinking about it but I am super grateful. I've been writing in my journal in blue ink manifesting this moment, communicating what I want and to be able to create on the company with Chalvar and Jawole. How brilliant, how amazing, how blessed I am to do that. So it really is just a full circle moment.

What story or emotional experience does The Holy Blues explore?

Monteiro: The Holy Blues touches on the human experience at large. I feel like it does a really beautiful job of looking at where we come from as a people, the inception of this country, and the journey of Black folks in this country. We're talking about a very charged and violent start and how we take all of that information and turn it into something triumphant and jubilant and beautiful.

Figgins: Through life, we have these hills and valleys, our human suffering and our pleasure, our delight, our bliss, our joy, and The Holy Blues is a chance to watch that journey of a group of people—a community, of course, but all individuals—how they tackle the challenges of bringing themselves up out of whatever pain they may be in, out of whatever life throws at them, and how they are able to create something beautiful out of it.

Can you talk about what role blues music plays in this piece?

Monteiro: Absolutely. For me, the blues is a perfect example of turning trauma and pain into an experience that is clearly articulated for other people to understand, even if it's just through sound. I think that we can clearly feel what the artist is going through or conveying. And I think dance is the same type of vehicle where even through a movement language that is specific to a choreographer, we can see a very clear portrait of emotion that allows people to see themselves and question or challenge what it is that they know to be true for themselves.

There is also a blue door as part of the set in this piece. Is there any special relevance to the color blue?

Figgins: We have been working deeply with Imani Perry's amazing book Black in Blues: How a Color Tells the Story of My People. It was just perfect because this is what the ballet is about, how blue tells the story of our people. I read this quote in rehearsal today by Richard Wright: "The most astonishing aspect of the blues is that, though replete with the sense of defeat and down-heartedness, they are not intrinsically pessimistic. Their burden of woe and melancholy is dialectically redeemed through sheer force of sensuality into an almost exultant affirmation of life, of love, of sex, of movement, of hope. No matter how repressive was the American environment, the Negro never lost faith in or doubted his deeply intimate capacity to live. All blues are a lusty lyrical realism charged with taut sensibility.” I love that quote, because that's what we are trying to create. It's the polarity of life. There's the bad and the good and there's hot and cold, but also the melt. Within your cries and your wails there is your breath. It's all affirmation of life, and so to have that life coursing through your veins when you are in that deep melancholy, having that life force energy is a reminder that with another breath is another opportunity.

Monteiro: Blue has so many meanings. I think blue is the only color that is endless. I think in nature we can see the expanse of the sea. We see the skies. The blue door in the work functions as a portal. It represents to me the sea and the fate that some of our ancestors chose to give themselves to the sea instead of committing to this other fate that was out of their hands. Or looking at the hopefulness of a blue sky, no matter how dark it gets, even when the moon goes up and the sun goes away, there's still hope for tomorrow. I think blue reflects the range of emotion as well, hopefulness and despair and everything that exists between the two.

The Holy Blues is inspired by the ring shout and the door of no return. Can you describe what each is and what it means to you personally?

Monteiro: The door of no return for enslaved people was the last point of contact that they had with the mother continent of Africa. In thinking about the door of no return, it was also the birth of what is called “the new Black,” where no matter where you came from in Africa, we were all brought over together and had to make sense of this new world. Thinking about all the languages that were lost in an effort to build a new one, all the ways that we would praise or have rites of passage that were lost in an effort to keep up with the systems we now saw as our reality. The ring shout was born out of that, a time where our spiritual practices were made illegal, when drumming was illegal, shouting and congregating was illegal. So how do we see the ring shout being born out of ingenuity, seeing how folks came together and found a way to combine voice and body and sound and find a way to protest, how do we give honor to that, to their higher being? The ring shout is also evidence of life, because I'm here congregating with others and praying and sharing with others. I'm here to see another day and hopefully cause a change or to give somebody what it takes to get through the day.

Figgins: A lot of the dances out of the ring shout come from every diaspora that came over from the transatlantic slave ships. Those communities brought over their shared history, bringing over what they could remember from the motherland, from Africa. Coming together, all these different people are able to communicate through dance and movement and share that language. That community gathering is something that we see through time. We see the ring shout in the juke joint, we see dancers Lindy hopping, all the way up to the present day. From my personal archive I'm bringing the DC beat ya feet movement. That goes right alongside Go-Go, which for me feels like something out of DC that is super similar to the ring shout. What we have created in rehearsal is an ancestral DNA, allowing all of the dancers’ cultures to come and live within the space. So we have DC with beat ya feet, we have people from Memphis jerking or people from Califronia c-walking. People from different places come together to have this moment to create something new.

Why does it feel important to tell this story now?

Figgins: This piece feels important to tell right now, because again, it's a life cycle. Often when we think about the blues, we think back to the 1960s and 1950s and earlier, and all that was going on socially and culturally in the world during those times. A lot of times, even thinking about how we look at photography or images from the past, our history of things is in black and white, when it was actually really close to what is happening now in the timeline. We're not that far away from that time. I think The Holy Blues, with everything that is going on socially, politically, and culturally in the world right now, there is a heaviness that can be felt and I think it's a wonderful time to, as Mr. Ailey would say, put a microscope to that feeling. Grab the feeling of the blues that is strong through our history and have it resonate for what this generation is going through right now.

Monteiro: As we understand that art imitates life, I think just looking at the scope of the world right now and seeing the liberties and the rights that are being challenged and stripped away. I think it's time to really think about where we come from and how this isn't the first time that we've come into contact with oppressive systems. I think it's a really beautiful time to think about the roots of blues and music and the roots of art forms that talk about transmuting something painful into beauty.

Is there anything else that you really want the audience to know before seeing the work or what you hope they might take away afterwards?

Monteiro: After seeing this work, I'm hoping that audiences reflect on their own history, their experiences, and how it is that they handled hardship. I think a big takeaway from this work, as someone that has the privilege of creating a work on their colleagues and also being able to see them from a distance, I'm reminded of just how beautiful community really is and how we're never in anything alone. Even with our very individual experiences and identities, know you're never alone.

Figgins: I'm very grateful for this opportunity. I think it was a wonderful chance to work with the dancers as well. They're informing the process so much by being so giving and open. Having such a diverse group of dancers who really pour their life experiences into the work, their personal archives, how they're so willing to give, really just helps build the world. This moment should be a breath of fresh air, an opportunity to turn the page.

Hero Credit: Chalvar Monteiro and Samantha Figgins rehearsing The Holy Blues with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Photo by Alice Castro.